The history of the Sasakawa Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease) Initiative begins with Ryoichi Sasakawa and the establishment of the Japan Shipbuilding Industry Foundation (now The Nippon Foundation) in 1962. Sasakawa’s bold idea to generate revenue through motorboat racing and to direct a portion of the revenue to philanthropic activity made possible a uniquely flexible grant-making organization. Driven initially by Sasakawa’s personal interest in reducing suffering associated with Hansen’s disease, The Nippon Foundation developed a strong commitment to internationally coordinated efforts to eliminate the disease and problems associated with it.

A lunch meeting in 1973 connected Ryoichi Sasakawa to Morizo Ishidate, a professor of pharmaceutical science at the University of Tokyo. Ishidate was by then well-known for synthesizing Promin, the first drug shown to be effective against Hansen’s disease. He did this based on a scrap of information that he obtained during World War II, and he managed a tiny trial showing Promin’s effectiveness before a laboratory in the US made the drug globally available. At the lunch, Sasakawa proposed the creation of a foundation to eliminate leprosy from the world and asked Ishidate to chair the organization. Their agreement led quickly to the formation of the Sasakawa Memorial Health Foundation (now Sasakawa Health Foundation) in 1974.

The history and achievements of The Nippon Foundation (TNF), Sasakawa Health Foundation (SHF), and the WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination (GWA) described here comprise the foundation of the Sasakawa Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease) Initiative. Important themes include commitment to a public health approach and respect for individuals who have experienced the disease.

Public health

Even though the Sasakawa Health Foundation (SHF) was established to work on Hansen’s disease, the founders did not use the name of the disease in the organization’s name. Their choice to use the word “health” reflected their belief that national governments should take responsibility for controlling the disease and integrate treatment with general health services. At the time, many countries had effectively outsourced Hansen’s disease care to private agencies. Each of these agencies had their own approach and would negotiate with governments so that they could offer their own services. As a result, public health workers lacked both incentive and opportunity to develop knowledge and skills related to Hansen’s disease. SHF aimed to build the capacities of national health ministries by sponsoring training and providing drugs, equipment, and funding. At the time, in the field of Hansen’s disease control, this strategy of a private agency getting involved in building up national programs instead of offering its own services was unprecedented.

Ishidate, SHF’s first chair, felt strongly that the Foundation’s work should be based on up-to-date scientific knowledge and practice. Additionally, both Ishidate and Sasakawa acknowledged that SHF would be a relative newcomer to the field of Hansen’s disease control, and they took the stance that SHF should start out by learning as much as possible from organizations and individuals who already had years of experience. They especially valued the perspectives of World Health Organization (WHO) experts, member organizations of the European Federation of Anti-leprosy Organizations (ELEP), and persons actually running leprosy programs in endemic countries. Regionally, Ishidate and Sasakawa had decided to focus on East and Southeast Asia, and so their first priority after the founding of SHF was learning about existing problems in endemic countries in this region and identifying possible solutions based on the latest thinking in science and public health.

Reception for The 1st Seminar on Leprosy Control Cooperation in Asia (Tokyo, Japan, 1974).

International conferences

In 1974 and 1975, Sasakawa Health Foundation (SHF) organized and hosted two international seminars held in Tokyo on leprosy control in Asia. Representatives of 10 leprosy-endemic countries in Asia (Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam), along with delegates from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Federation of Anti-leprosy Organizations (ELEP), joined Japan-based experts to share their experiences and discuss leprosy control measures. The discussion highlighted what was called at the time a “manpower problem”—a shortage of Hansen’s disease control personnel and a lack of knowledge and skills. Accordingly, SHF organized a series of nine follow-up workshops designed to raise the capacities of national Hansen’s disease programs:

- Training of Leprosy Workers in Asia (Bangkok, 1976, 1979, 1982)

- Chemotherapy of Leprosy in Asia (Manila, 1977)

- Leprosy Control in Asia (Jakarta, 1977)

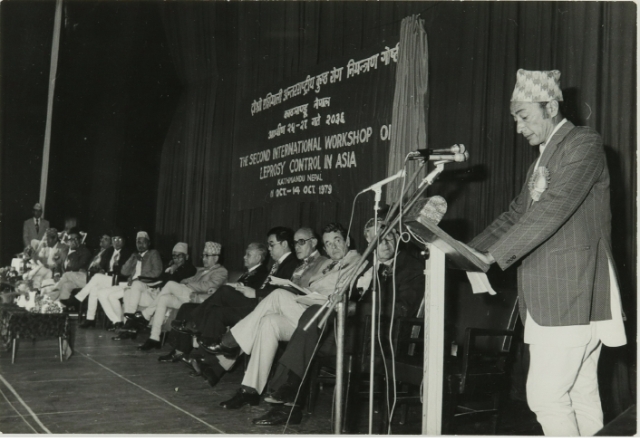

theme: role of voluntary agencies in national leprosy control programs - Leprosy Control in Asia (Kathmandu, 1979)

theme: role of community - Leprosy Control in Asia (Taipei, 1980)

theme: case-finding and case-holding - Leprosy Control in Asia (Kuala Lumpur, 1982)

theme: reporting and evaluation - Leprosy Control in Asia (Singapore, 1983)

theme: control in urban areas

The Second International Workshop on Leprosy Control in Asia (Kathmandu, Nepal, 1979)

Achievements:

- Trained national leprosy control personnel

- Detailed minutes of each workshop were written in English and distributed as a textbook for training

- Provided opportunities for information exchange and experience sharing among national program managers of endemic countries

- Strengthened and nurtured partnerships among attendees

- Improved the status of leprosy program personnel

By 1983, the frequency of international meetings had increased to the point that SHF mostly stopped organizing conferences of its own. SHF shifted to partnering and financial sponsorship, and was especially active in co-sponsoring conferences with WHO. Of the approximately 40 international leprosy conferences sponsored or co-sponsored by SHF, the following are particularly noteworthy.

- Epidemiology of Leprosy (Geilo, 1981)

- Immunology of Leprosy (Oslo, 1985)

- Elimination of Leprosy (Hanoi 1994, New Delhi 1996, Abidjan 1999)

The 2nd International Conference on the Elimination of Leprosy (New Delhi, India, 1996).

Importance of the 1977 workshop on chemotherapy held in Manila

From the mid-1970s, when SHF was just beginning to decide on strategies, the bacillus M. leprae started showing increased resistance to dapsone therapy. This meant that even patients who had responded well to treatment could relapse in time with fully-resistant M. leprae. Leprosy control methods that had been developed over the past 30 years were at risk of becoming completely ineffectual. Experts knew of the risk and some had started testing different combinations of drugs, but the World Health Organization (WHO) was not, at this point, advocating a worldwide shift to a new treatment regimen. In 1977, SHF provided a forum for discussion with an international workshop titled Chemotherapy of Leprosy in Asia.

In addition to chemotherapy experts, participants in the workshop included national leprosy control managers and representatives from WHO and various NGOs. Following five days of discussion, the workshop concluded with a recommendation for immediate abandonment of dapsone monotherapy and implementation of combination therapy using two or more drugs.

Dr. Yo Yuasa (standing), SHF’s medical director, participating in the 1st International Workshop on Chemotherapy of Leprosy in Asia (Manila, Philippines, 1977).

The points raised at this five-day workshop contributed to WHO’s decision to convene a Study Group on Chemotherapy for Leprosy Control in 1981. The group’s report, published in 1982, stated clearly that the only way to prevent the spread of dapsone-resistant leprosy was to use multidrug therapy (MDT), and recommended a standard regimen of rifampicin, dapsone, and clofazimine.

Elimination of leprosy as a public health problem based on MDT

In 1989, SHF’s medical director, Dr. Yo Yuasa, while acting as a short-term consultant for the World Health Organization (WHO), joined preparations in Manila for a Western Pacific Region conference on leprosy. Responding to a request from the regional director, Dr. Sang Tae Han, Yuasa and the regional advisor for chronic communicable disease control, Dr. Jong-wook Lee, studied newly collected data on the current leprosy situation in each member country. They concluded that intensive nationwide implementation of MDT could reduce the prevalence rate of each country from around 1/1,000 to 1/10,000 within 10 years.

Dr. Yo Yuasa, SHF’s medical director and short-term consultant for the World Health Organization (WHO), in serious discussion with Dr. Sang Tae Han, WHO Regional Director for the Western Pacific Region.

Yuasa and Lee knew that national health authorities would need to be convinced of the value of treating every leprosy patient in their country with MDT. They needed an effective catchphrase. They found inspiration in a pamphlet about tuberculosis that chemotherapy expert Dr. Robert Jacobson had brought with him from the United States. Based on the phrase “elimination of tuberculosis” in the pamphlet’s title, they called for “elimination of leprosy as a major public health problem.”

They were successful. Their proposal received approval from all national program managers present at the conference. Han also gave full support, and prevalence of less than 1/10,000 population at the national level became a standard indicator for leprosy control programs in the Western Pacific Region.

The Western Pacific Region had forged ahead without consulting the head of the Leprosy Unit, Dr. S. K. Noordeen, in Geneva. In retrospect, it is possible to see that they provided a model for a worldwide movement. Two years after the conference in Manila, in 1991, the 44th World Health Assembly adopted a resolution to “eliminate leprosy as a public health problem” by the year 2000, and elimination was defined as “the reduction of prevalence to a level below one case per 10,000 population” at the global level.

SHF and TNF role in provision of MDT drugs

In the mid-1970s, when the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) discontinued dapsone aid for Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines, SHF stepped up to become the primary provider for the region. From 1974 to 1976, SHF provided dapsone to Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Korea, Nepal and Taiwan. As evidence of dapsone resistance mounted, SHF added clofazimine in 1977 and rifampicin in 1978, prior to the publication of the 1982 WHO study group report recommending multidrug therapy (MDT).

After the WHO report was published, SHF expanded the number of countries receiving SHF drug-related support. TNF also responded promptly and earmarked a portion of its annual donation in 1982 specifically for activities related to MDT implementation.

The successful spread of MDT treatment depended in part on packaging of the drugs. Health workers needed to be able to deliver treatment easily; patients needed to be able to ingest drugs daily; and the drugs had to be protected from insects and other environmental challenges. In addition, there needed to be a guarantee that the drugs would be given to leprosy patients and not reapportioned to patients with other diseases, such as tuberculosis.

The solution came from SHF’s medical director, Dr. Yo Yuasa. Asked in 1982 by WHO to explore the possibility of implementing MDT in Vietnam and the Philippines, Yuasa sought permission from the secretary of health in the Philippines for a pilot study. As he made his case for the study’s feasibility, he found himself saying on the spot that the drugs could be packaged in calendar blister packs for easy use and protection. This had not been done before for leprosy MDT treatment, and facing certain financial loss, the manufacturer initially refused. With helpful pressure from the local president of the company and the regional director of WHO, the blister packs were made, and a precedent for MDT packaging was set. Calendar blister packs became standard and are still used today.

Calendar blister packs contain MDT in daily doses.

By 1994, SHF was supporting MDT implementation in over 20 countries, including some in Africa and South America. The prevalence rate at the global level was dropping, but it was thought that getting to 1 case per 10,000 population by the year 2000 would be difficult. At the International Conference on the Elimination of Leprosy as a Public Health Problem held in Hanoi in July 1994, Dr. Hiroshi Nakajima, WHO Director-General, warned that the resources required to reach and cure the remaining patients would be greater than those required so far. Following his statement, Yohei Sasakawa, as President of The Nippon Foundation, announced that TNF would provide WHO with US$ 10 million annually for five years (1995-1999) so that MDT could be administered to all leprosy patients worldwide free of charge. This donation liberated countries from concerns about costs of the drugs and so accelerated the pace of MDT implementation. Partly because of this support, the ambitious goal of eliminating leprosy as a public health problem at the global level was reached, on target, by the end of 2000.

Leprosy-related research

Advocacy

WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination

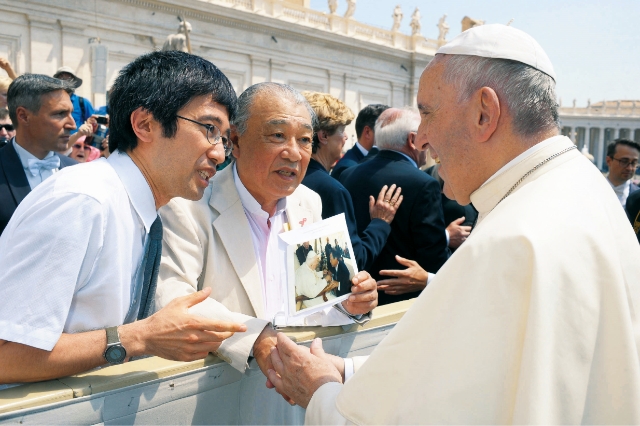

In 2001, Yohei Sasakawa was appointed WHO Special Ambassador to the Global Alliance for Elimination of Leprosy (GAEL). Following GAEL’s dissolution, the appointment was retitled WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination. In 20 years of serving in this role, Sasakawa has visited over 90 countries to learn about and raise awareness of the challenges associated with the disease. His self-assigned tasks include:

- Meeting and talking directly with the political leaders of countries where leprosy is endemic

- Promoting correct knowledge and understanding of leprosy through media and giving positive attention to community-based awareness campaigns

- Strengthening partnerships by bringing together governments, medical professionals, non-governmental organizations, health workers, organizations of persons affected by leprosy, and other stakeholders

- Field visits to endemic areas, including remote locations, to meet directly with persons affected by leprosy, family and community members, and frontline health workers

WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination Yohei Sasakawa delivers a message to Pope Francis at St. Peter’s Square (Vatican City, 2016).

Newsletter

To document and support Yohei Sasakawa’s efforts as WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination, SHF, with support from TNF, began publishing a bimonthly newsletter in English in 2003. The readership includes health workers and health ministries, WHO, non-governmental organizations, foundations, embassies, world leaders, and individuals who are concerned about the issues related to leprosy. The 100th issue was published in May 2020.

Front covers of the first (April 2003) and 100th (May 2020) issues of the WHO Goodwill Ambassador’s Newsletter for the Elimination of Leprosy. Along with a redesign for the 101st issue (December 2020), the newsletter was retitled WHO Goodwill Ambassador’s Leprosy Bulletin.

Human rights

In 2003, Yohei Sasakawa visited the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva to request that the United Nations (UN) take specific measures to resolve discrimination related to leprosy. This reflected growing awareness that a medical cure was not going to eliminate stigma and discrimination.

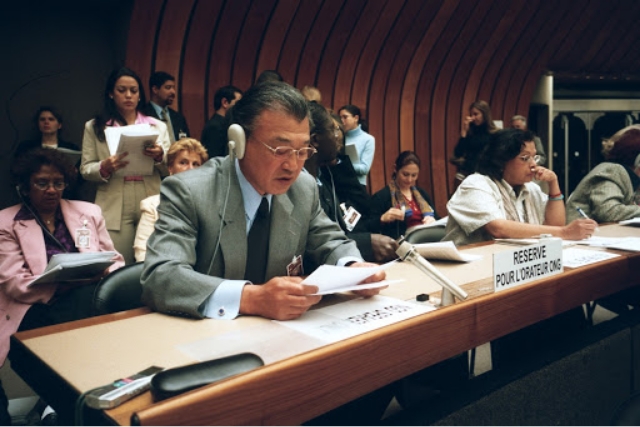

The following year, Sasakawa addressed leprosy as a human rights issue at the regular session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. Five months later, the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights resolved to conduct a study of leprosy from a human rights perspective.

Yohei Sasakawa addresses the 60th session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in order to draw attention to leprosy as a human rights issue (Geneva, Switzerland, 2004).

When Sasakawa turned over his speaking time to four persons affected by leprosy from India, Ghana, and Nepal in 2005, this became the first time that persons affected by leprosy addressed a formal session of the United Nations. The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights adopted a resolution that calls for ending discrimination against persons affected by leprosy.

Nevis Mary, a person affected by leprosy from India, speaks at the 57th session of the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (Geneva, Switzerland, 2005).

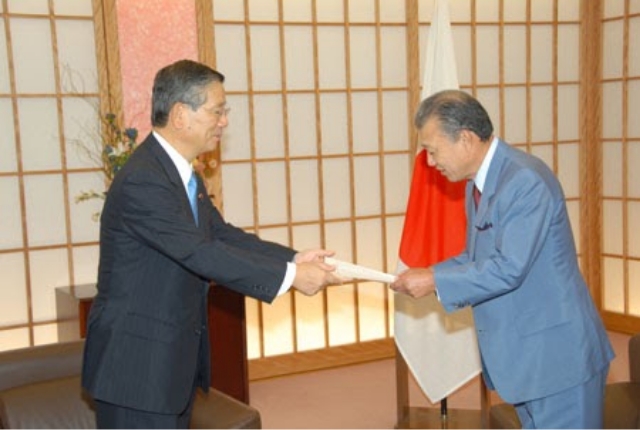

As the Human Rights Commission reorganized into the Human Rights Council in 2007, TNF cooperated with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan to keep attention on leprosy and human rights. The Japanese government resolved to make appealing to the international community to abolish discrimination towards leprosy one of the pillars of Japan’s foreign policy. Recognizing Yohei Sasakawa’s capacity for contribution, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs appointed him Japanese Government Goodwill Ambassador for the Human Rights of Persons Affected by Leprosy.

Minister of Foreign Affairs Nobutaka Machimura presents Yohei Sasakawa with a letter appointing him Japanese Government Goodwill Ambassador for the Human Rights of Persons Affected by Leprosy (Tokyo, Japan, 2007).

In 2008, the Japanese government’s proposal for “elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy and their family members” was unanimously adopted and co-sponsored by 59 countries. The resulting resolution requested the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) Advisory Committee to formulate a draft set of principles and guidelines.

In 2010, the UNHRC unanimously adopted the principles and guidelines, and invited the UN General Assembly to consider the issue of leprosy-related discrimination. Later in the same year, the General Assembly adopted a resolution encouraging all governments, institutions, and relevant actors in society to “give due consideration” to the principles and guidelines in the formulation and implementation of their policies and activities.

To spread awareness of the principles and guidelines, TNF organized five regional symposiums held in Brazil (2012), India (2012), Ethiopia (2013), Morocco (2014), and Switzerland (2015). The final symposium included presentation of a follow-up report on the resolution and proposals for an action plan.

African Regional Symposium on Leprosy and Human Rights (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013).

Global Appeal

In 2006, WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination Yohei Sasakawa, with the support of TNF, launched the Global Appeal to End Stigma and Discrimination against Persons Affected by Leprosy. Timed to coincide with World Leprosy Day, the Global Appeal is both an annual event and a written statement calling for an end to prejudice and human rights violations against persons affected by leprosy. In order to spread awareness and encourage solidarity, TNF seeks a new set of individuals and organizations from different fields to attend the event and endorse the statement each year.

12th Global Appeal to End Stigma and Discrimination against Persons Affected by Leprosy (New Delhi, India, 2017).

Empowerment

Organizations of persons affected by Hansen’s disease

The International Association for Integration, Dignity, and Economic Advancement (IDEA), established in 1994, was the first international organization composed primarily of individuals personally affected by Hansen’s disease. Inspired by IDEA’s example, other groups of persons affected by leprosy formed around the world. Members raised their own voices to advocate for release from poverty, equal opportunity, access to treatment for disabilities, and the restoration of dignity.

Since 1995, SHF has provided a wide range of support to organizations of persons affected by leprosy in various countries, including China (HANDA), Ethiopia (ENAPAL), Indonesia (PerMaTa), the Philippines (CLAP), and Colombia (Corsohansen). TNF supports organizations in India (APAL) and Brazil (MORHAN). The activities of these organizations include awareness raising to correct prejudice and discrimination in society, support for socio-economic independence, cooperation with governments to secure access to medical and welfare services, and promotion of the development of administrative capacity to ensure the continuation of those services. In Vietnam and Indonesia, SHF has supported the development of model cases showing the potential for integrated rehabilitation of people with leprosy-related disability.

Chairman Paulus Manek (right) and Vice Chairman Al Qadri (left) of PerMaTa, an Indonesian organization of persons affected by leprosy (Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017).

APAL and S-ILF

In 2006, TNF contributed to the founding of the Association of People Affected by Leprosy (APAL) , a national networking organization of persons affected by leprosy in India. APAL’s mission is to work for the socio-economic empowerment and welfare of persons affected by leprosy. In the same year, TNF supported the establishment of Sasakawa-India Leprosy Foundation (S‒ILF) in New Delhi. S-ILF’s purpose is to help persons affected by leprosy and their families, especially those living in segregated colonies, to move out of begging and dependence on donations and into self- or wage-employment.

Sasakawa-India Leprosy Foundation (S-ILF) goat breeding project at the Jay Durga leprosy colony (Uttar Pradesh, India, 2013).

Guidelines for strengthening participation of persons affected by leprosy in leprosy services

In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for South-East Asia published “Guidelines for strengthening participation of persons affected by leprosy in leprosy services.” Developed in consultation and active partnership with persons affected by leprosy, the Guidelines are meant to help service providers recognize and make use of the expertise of individuals who have experienced leprosy. SHF has been supporting implementation of the Guidelines since 2014.

Cover of “Good practices in strengthening the participation of persons affected by leprosy in leprosy services” (2018), a publication supported by SHF as a follow-up to Guidelines promulgated by the World Health Organization.

Global Forum of People’s Organizations

In 2019, SHF and TNF jointly sponsored a Global Forum of People’s Organizations on Hansen’s Disease. Starting from continent-based assemblies in Asia, Africa, and South America, the Global Forum brought together persons affected by leprosy from 18 countries representing 23 organizations. For four days in Manila, organization members shared plans, ideas, and experiences, and participated in capacity-building workshops. The timing and location of the Forum was chosen so that delegates could stay in Manila and present their recommendations at the 20th International Leprosy Congress.

Group photo of participants in the Global Forum of People’s Organization on Hansen’s Disease (Manila, Philippines, 2019).

History preservation

With the success of MDT treatment and the integration of leprosy care into general public health programs, artifacts (documents, objects, buildings) from leprosaria and colonies were being dispersed, abandoned, or destroyed. Persons affected by leprosy with memories of the years of compulsory isolation were aging. Since the late 1990s, SHF has been leading a movement to preserve artifacts and oral histories so that future generations can learn about the many ways that humans have responded to the disease. SHF encourages spotlighting actions taken by persons affected by leprosy, which include inspiring instances of self-advocacy and resistance to injustice.

Database of world leprosy history

Grants for preservation and research

Since 2004, in order to preserve the histories of leprosy around the world, SHF has been financially supporting and cooperating with experts and leprosaria administrators to preserve historical artifacts and oral histories of present and former residents. As of 2020, SHF has supported history preservation work in Spain, Portugal, Romania, India, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, China, Japan, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Egypt. In Southeast Asia and Central and South America, SHF has also cooperated on comprehensive historical research that examines leprosy from multiple angles, including welfare policy and religion.

Hospital Colónia Rovisco Pais, Higienização do arquivo do Serviço Social (Tocha, Portugal, 2018). All rights reserved.

Heritage of Humanity symposium series

In 2012, SHF and TNF sponsored the first Leprosy/Hansen’s Disease History as Heritage of Humanity International Symposium. Held in Tokyo, the purpose of the Symposium was to promote preservation of artifacts and oral histories on a global scale so that future generations could learn from humanity’s experience with the disease. Five follow-up symposiums were held in various locations in Japan over the three-year period 2015-2017. Recognizing that history preservation requires the involvement of national governments, experts, and persons who have experienced living in a sanitarium, SHF invited representatives from all three of these stakeholder groups.

Published minutes from the International Symposium on Hansen’s Disease/ Leprosy as Heritage of Humanity held in Okayama, Japan (2017).

Published minutes from the International Symposium on Hansen’s Disease/ Leprosy as Heritage of Humanity held in Okayama, Japan (2017).Support for network building

In 2019, SHF supported the first European meeting for the preservation of historic leprosy sites. Representatives of six organizations from four countries met at Fontilles Sanatorium in Spain. Plans were made for a second meeting to be held in Portugal in 2020, but it had to be postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Plans are underway to hold something in fiscal year 2021—entirely online if necessary— so that the network continues to strengthen and benefit all members.

European networking conference at Fontilles (València, Spain, 2019)