Special series to recognize 50-year partnership

With this issue, the Leprosy Bulletin is launching a six-part series in relation to the upcoming 50th anniversary of the partnership between the World Health Organization (WHO) and The Nippon Foundation (TNF)/Sasakawa Health Foundation (SHF) for the elimination of leprosy.

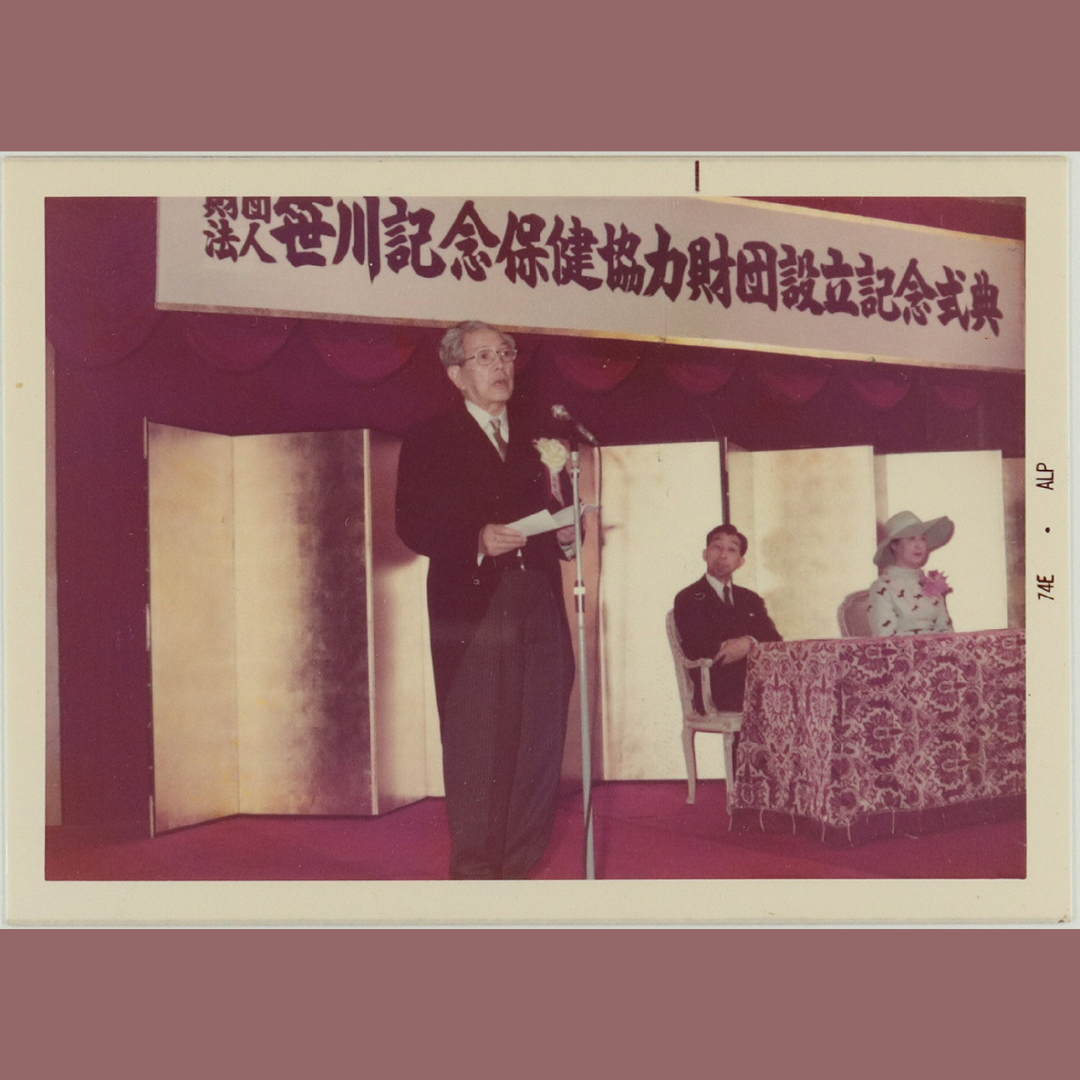

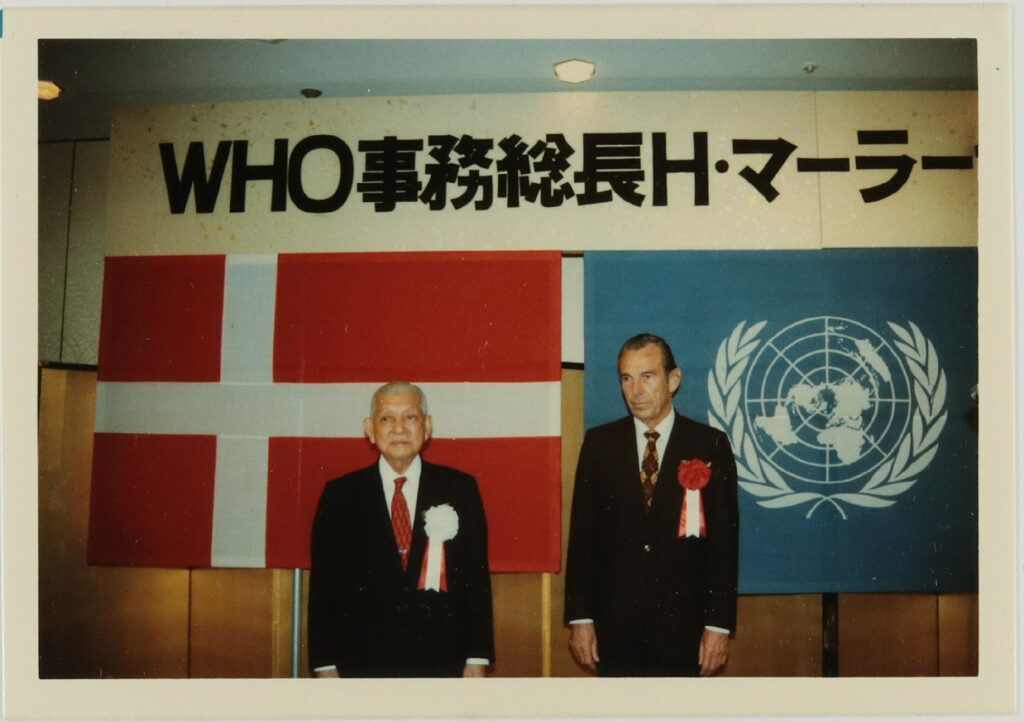

The partnership began in 1975 when Ryoichi Sasakawa, the first chairman of TNF and co-founder of SHF, donated US$1 million to WHO to eradicate the disease worldwide. For five years (1995–1999), TNF provided WHO with US$10 million per year so that multidrug therapy (MDT) could be distributed to all patients free of charge. Yohei Sasakawa has been the WHO Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination since 2001.

Based on the theme of partnership and collaboration, the series will feature people who have worked closely with TNF/SHF over the past 50 years. The Bulletin will ask them to reflect on their experiences with the foundations and to share their thoughts on the place of TNF/SHF in the global fight against leprosy.

Interview with Dr. David Heymann

Dr. David Heymann is currently Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and a Distinguished Fellow at the Centre on Health Security at Chatham House, London. From 1988 to 2009, he was based at WHO headquarters in Geneva, on secondment from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States. For five years of his time with WHO, from 1998 to 2003, he had overall responsibility for WHO’s leprosy program as the Executive Director of the Communicable Diseases Cluster. He held this post at a time when WHO was working to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem at the global level by the year 2000, based on a resolution adopted by the 44th World Health Assembly in 1991.

LB (Leprosy Bulletin): When did you join the World Health Organization (WHO), and in what capacity?

DH (Dr. David Heymann): I joined WHO in 1988. After 13 years in Africa and two years in India, I was seconded from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States. First I worked on the AIDS program, and then in 1995 I was asked by the Regional Director in Africa to help out with the Ebola outbreak, because I had been at the first and second outbreaks, and this was the third. When I came back, the Director General (DG) asked me to set up a new program on emerging infections. Two years later, I became Executive Director of Communicable Diseases under a new DG, Gro Harlem Brundtland. At that time, the leprosy program came under my mandate. That was in 1998.

LB: What was your first encounter with TNF/SHF?

DH: It was through a director who worked for me, Dr. Maria Neira. She knew Mr. Sasakawa [Yohei Sasakawa, the current Goodwill Ambassador] quite well, and she introduced me to Dr. Yuasa [Yo Yuasa, medical director of SHF], and I was then invited to the annual meeting of SHF in Japan. There I met Mrs. Kay Yamaguchi, Professor Kenzo Kiikuni, Mr. Tatsuya Tanami [executive director of TNF], and Mr. Sasakawa.

LB: What was your impression of TNF/SHF?

DH: I think they were a real engine for the leprosy control program and that they were an engine that moved WHO towards stronger leprosy control through various means, including World Health Assembly resolutions. They were very important in calling attention to leprosy through whatever they did.

LB: This was the era of the Global Alliance for the Elimination of Leprosy (GAEL), which was formed in 1999 to maintain the momentum against leprosy beyond 2000 and to help all countries eliminate the disease as a public health problem. GAEL eventually disbanded in 2003 due to disagreements among its members. What are your memories of that time?

DH: There was quite a bit of tension in the program. TNF [1995–1999], and later Novartis and the Novartis Foundation [2000–present], were providing medications at no cost. There were other NGOs that were also providing medications. Medications seemed to be the key to fundraising for these NGOs, and so when these donations began, they were not very happy. That created some tension. There was also tension over who should lead the program, and who should not, and I think there was quite a bit of resentment from some of the NGOs toward the WHO. I saw my role as trying to mediate the many tensions that were occurring. But tensions often develop, and the only way to deal with them is to sit around the table with everyone.

LB: The WHO–TNF/SHF partnership will be 50 years old in 2025. What do you think has contributed to its longevity?

DH: To me it was a clear, constant and unwavering vision that drove the partnership. TNF/SHF had a vision. It changed over time: as I understand it, initially it was based purely on treatment and diagnosis; then it became more about human rights and people affected by leprosy, or Hansen’s disease, adding an important element to the already important work of providing for diagnosis and treatment.

Mr. [Yohei] Sasakawa has been a real champion for leprosy elimination and has been able to meet with very influential people, including heads of state, all over the world. He is an amazingly dynamic and energetic leader who has done many good things and continues to generate the energy behind the leprosy program.

LB: Do you think it is unusual for private-sector partners to support a single disease program for so long?

DH: There are others. In polio eradication, there is Rotary International. It has been a faithful partner since 1988. There is the onchocerciasis (river blindness) partnership, which depends on the Mectizan Donation Program, supported by the Merck Foundation. So the Sasakawa foundations’ partnership with WHO is not unique, but it’s very important, especially given that leprosy is often neglected because it is a high disability disease, as opposed to a high mortality disease or an emerging infection, and high disability diseases don’t tend to attract a lot of donor financing.

LB: In their partnership with WHO, TNF and SHF have always attached importance to having numerical targets in the fight against leprosy. What are your views on targets?

DH: Having targets that say this is going to happen, and this is going to happen by a certain date or this is what we are aiming for makes it possible to pull in short-term partners to provide drugs, whether for leprosy or for onchocerciasis or other diseases. But long-term sustainability is really important to think about at the same time. I used to wonder, and I still do, what would happen if there was a decision by Novartis or TNF/SHF to stop contributing to leprosy control. I don’t believe that WHO would be able to continue on its own because of many competing priorities, especially those with high mortality.

LB: How do you view the progress made against the disease and the prospects for the future?

DH: I like to talk about windows of opportunity, and I think there is a window of opportunity to really reduce the prevalence and incidence of leprosy to a very low level, where it could theoretically disappear in the future. However, it is important to take advantage of this window of opportunity now when it exists. The same applies to any other disease. If there is a window of opportunity because all the parts fall in place as they have for leprosy, it is important to take advantage of it and hope that the window remains open long enough to have an impact.