Dr. Venkata Ranganadha Rao Pemmaraju

Acting Team Leader, Global Leprosy Programme

World Health Organization (WHO)

Dr. Pemmaraju has decades of experience in all aspects of leprosy control. His technical and administrative knowledge is balanced by time spent with persons affected by the disease. As the acting team leader for WHO’s Global Leprosy Programme, he works to ensure that the disease burden continues to decline in all countries.

Somalia, located in the horn of Africa and an important commercial center in antiquity, has an estimated population of 16.5 million people (2021). Agropastoralism remains the most common lifestyle, along with some nomadic livestock herding. “Elders” influence decisions and actions at home and in the community. Prolonged war and civil conflict compounded by famine for over three decades caused population movement. Life expectancy is 56 (2021); the Human Development Index is low (0.361 out of 1 in2019); and the Gender Inequality Index is very high. Communicable diseases, including leprosy and other neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), are clustered in central and southwest regions of the country as endemic pockets. In recent years, however, a number of new leprosy patients were reported from northern regions as well, which can be attributed to the displacement of people. Reproductive health problems, malnutrition, non-communicable diseases, and mental health issues have also been reported.

Casho, a mother of two children living in a camp for internally displaced persons near Mogadishu, noticed a patch on her right hand when she was a child. The disease progressed and deformities were developed. She did not venture to move out for treatment as she could not afford treatment outside the camp. Prevailing stigma about the disease was also a barrier. She had to wait for over six years until staff from the federal government’s Ministry of Health and Human Services (FMOH) visited the camp. She received a leprosy diagnosis and was treated, but because there was a delay, disabilities could not be prevented. Casho’s story reflects the situation of leprosy services.

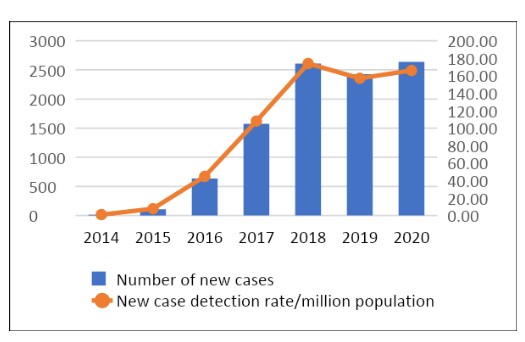

FMOH created a department for NTDs in 2015, and leprosy case detection campaigns were started in camps for internally displaced persons along with mobile skin clinics for the general population. The case detection was strongly backed by intense information, education, and communication campaigns. New cases increased from 14 (2014) to 2,638 (2020). Case detection trends demonstrate the commitment of FMOH to improve leprosy services and to reduce the leprosy burden. The statistics reflect the commitment of the staff and the political commitment and improved coverage of the program and quality of services. The increase in the number of new cases prompted WHO to include Somalia in the list of Global Priority Countries for leprosy and to advocate for more support from partners to the country. Sasakawa Health Foundation (SHF) supported the initiative of FMOH of Somalia to improve the coverage of leprosy services.

Early case detection to detect all new cases before deformities are developed and improved quality of medical treatment still need to be expanded to cover all regions of the country. Stigma against the disease is high in communities. As respected opinion-leaders, Elders can play a role in enhancing preparedness in the community and encouraging self-reporting of patients to seek treatment. Such community response complements efforts of FMOH to eliminate leprosy.

WHO’s technical assistance and supply of multi-drug therapy was instrumental in implementing leprosy services. Funds from SHF also copiously improved coverage of leprosy services. This is the time to organize persons affected by leprosy into a network to partner with FMOH for getting the voices of persons affected heard and combatting stigma against leprosy. FMOH commits to accelerating efforts to eliminate leprosy from the country. It is time that partners, including the persons affected and the community, join hands to strengthen efforts of FMOH to eliminate leprosy. There are great lessons to be learned from Somalia for implementing disease control activities in a very challenging situation against the backdrop of prevalent civil strife in a country.